Endovascular VNS: The Catheter-Based Revolution in Neuromodulation

How doctors are now stimulating the vagus nerve from inside your veins — no surgery required

Research Source: Journal of Neural Engineering 2023, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Reading Time: 9 minutes

Key Topics: Endovascular neuromodulation, catheter-based VNS, minimally invasive brain stimulation

2-4 Weeks Recovery time reduced to just days with endovascular approach

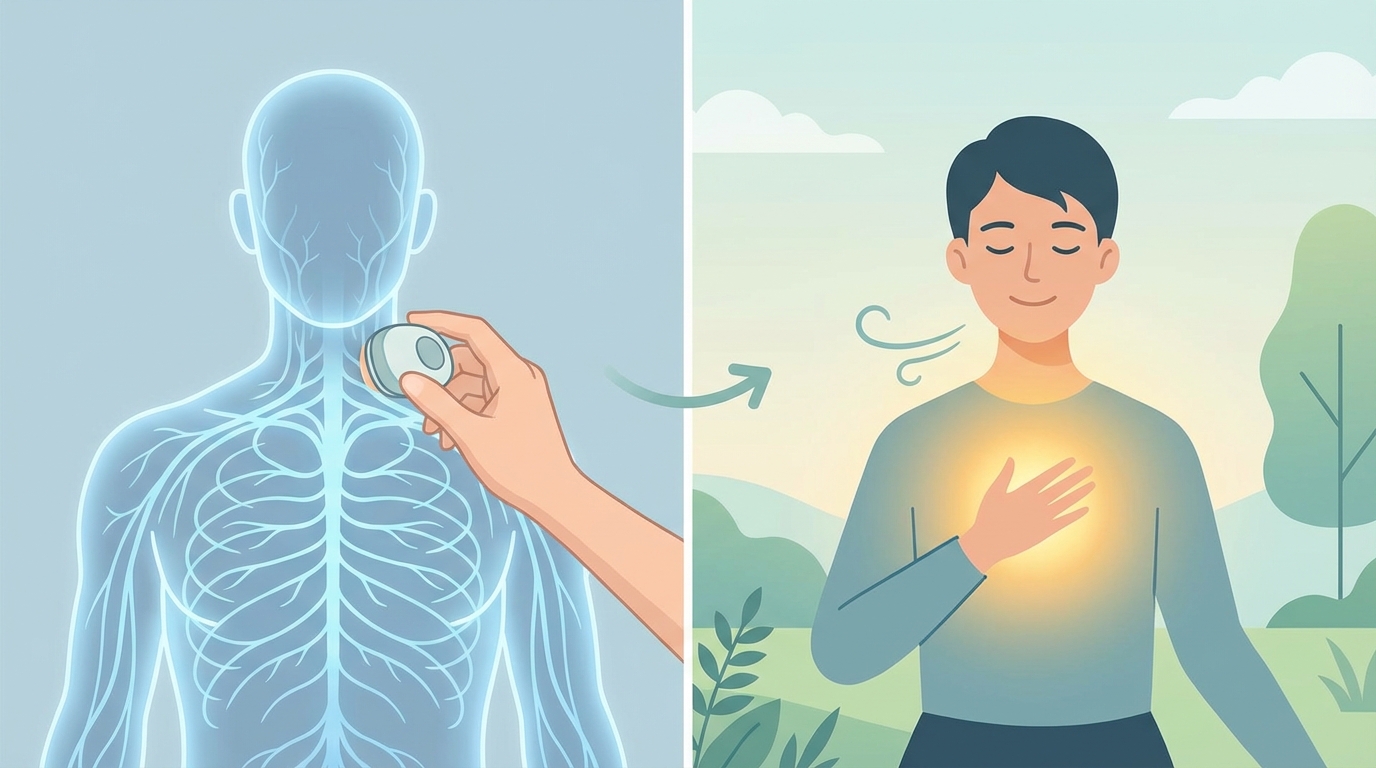

What if you could receive the full benefits of vagus nerve stimulation without the surgery, the recovery time, or the permanent implant? What if accessing one of the body's most powerful neural pathways was as simple as a standard catheter procedure that cardiologists perform thousands of times every day?

This isn't science fiction. A breakthrough study published in the Journal of Neural Engineering demonstrates that the vagus nerve can be effectively stimulated from inside the internal jugular vein — opening a completely new frontier in neuromodulation that's safer, faster, and potentially more effective than traditional approaches.

The Surgical Barrier

For over 25 years, vagus nerve stimulation has required open surgery. The procedure involves making an incision in the neck, dissecting through tissue layers, identifying the vagus nerve within the carotid sheath, wrapping a cuff electrode around the nerve, and tunneling a lead to a pulse generator implanted in the chest.

While this approach has helped tens of thousands of patients with epilepsy and depression, it comes with significant drawbacks:

Surgical risks: Infection, bleeding, nerve damage, and anesthesia complications

Recovery time: 2-4 weeks of healing and activity restrictions

Side effects: Two-thirds of patients experience hoarseness, coughing, or throat pain from motor fiber activation

Permanence: The device requires surgical removal if problems arise

Cost: $20,000-$40,000 for the device and surgical procedure

Limited access: Only patients with severe, treatment-resistant conditions qualify

These limitations have kept VNS out of reach for many patients who could benefit. But what if the solution has been hiding in plain sight — inside a vein that runs parallel to the vagus nerve?

The Endovascular Insight

The internal jugular vein (IJV) isn't just a passive drainage vessel for blood returning from the brain. It runs alongside the cervical vagus nerve for most of its course through the neck, separated by only a few millimeters of tissue. For decades, surgeons have viewed this proximity as an anatomical curiosity. Now, it's the foundation of a revolutionary approach.

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison asked a simple question: If the vagus nerve is only millimeters from the internal jugular vein, could we stimulate it from inside the vein? The answer, demonstrated in acute surgical experiments using swine models, is a resounding yes.

The Anatomy of Opportunity

Within the carotid sheath, the relationship between structures creates a unique opportunity:

Structure Position Distance to Vagus Nerve Internal Jugular Vein Lateral (outer) 0 mm (adjacent) Vagus Nerve Posterior (typically) N/A Common Carotid Artery Medial (inner) 2-5 mm

The vagus nerve lies directly against the posterior wall of the internal jugular vein at multiple points along the neck. This means electrical stimulation from inside the vein can activate the nerve with minimal current spread to other structures.

How Endovascular VNS Works

The procedure is remarkably similar to common cardiac catheterizations:

1

Vascular Access: A small puncture is made in the jugular vein (or femoral vein for femoral approach)

2

Catheter Insertion: A flexible catheter containing a multi-contact electrode array is advanced into the internal jugular vein

3

Imaging Guidance: Cone-beam CT fluoroscopy and ultrasound visualize the electrode position relative to the vagus nerve

4

Position Optimization: The catheter is maneuvered to locations where the nerve lies closest to the vein wall

5

Stimulation: Electrical pulses are delivered through the electrode contacts, activating the adjacent vagus nerve

6

Verification: Compound action potentials recorded from the nerve confirm successful activation

Breakthrough Findings

The research team, led by Evan N. Nicolai, demonstrated several critical findings:

1. Position Is Everything: The specific location of the stimulation electrode within the IJV dramatically affects activation efficiency. Optimal positions showed reliable vagus nerve activation, while suboptimal positions required several times higher current to achieve the same effect.

2. Motor Fiber Avoidance: Traditional cervical VNS often activates motor fibers running with the vagus nerve, causing the hoarseness, coughing, and throat discomfort that bother so many patients. By selecting specific stimulation sites within the vein, endovascular approaches can potentially target nerve segments where motor fibers have already branched off.

3. Feasibility Confirmed: Using an electrode array called the "Orion" system (originally developed for cardiac mapping), the team successfully recorded compound action potentials from the vagus nerve while simultaneously monitoring motor evoked potentials in neck muscles. This proved that endovascular stimulation reliably activates the target nerve.

Advantages of the Endovascular Approach

For Patients:

No open surgery — just a small puncture site

Recovery measured in days, not weeks

No neck incision or visible scar

Potentially fewer side effects (voice changes, cough)

Procedure is reversible — simply remove the catheter

No permanent foreign body if using temporary approaches

For Physicians:

Access to nerve segments unreachable by traditional surgery

Real-time imaging for precise positioning

Ability to test multiple locations before committing

Procedure familiar to interventional cardiologists/radiologists

Reduced surgical complications

Technical Challenges

While promising, endovascular VNS faces several technical hurdles:

Higher Stimulation Thresholds: Because the electrode doesn't directly contact the nerve, endovascular stimulation requires several times higher current than cuff electrodes. This demands more battery power and may limit stimulation parameters.

Positioning Precision: Success depends on accurately positioning the electrode at optimal sites. This requires advanced imaging (cone-beam CT) and specialized training.

Long-Term Considerations: Questions remain about:

Venous thrombosis risk from indwelling electrodes

Electrode stability over months or years

Device retrieval if needed

Chronic vessel wall effects

Comparison: Traditional vs. Endovascular VNS

Feature Traditional Cuff VNS Endovascular VNS Procedure Type Open surgery Catheter-based Anesthesia General Sedation or local Recovery Time 2-4 weeks 2-3 days Scarring Neck and chest incisions Small puncture site Side Effects Common (66% hoarseness/cough) Potentially reduced Reversibility Surgical removal Simple withdrawal Cost $20,000-$40,000 Estimated lower Status FDA approved Investigational

Future Applications

Beyond replacing traditional VNS, endovascular approaches open entirely new possibilities:

Temporary/Acute Stimulation: Patients could receive VNS during critical periods — post-surgery, during acute inflammatory episodes, or while tapering medications — without permanent implantation.

Rescue Therapy: For patients experiencing breakthrough seizures or acute depressive episodes, an endovascular approach could provide rapid intervention in emergency settings.

Diagnostic Tool: Temporary endovascular stimulation could predict which patients will respond to permanent VNS implantation, avoiding unnecessary surgeries.

Expanded Access: Lower-risk procedures could extend VNS to patients with milder conditions who don't qualify for traditional surgery.

The Road Ahead

The University of Wisconsin research represents proof-of-concept in animal models. Human trials will need to establish:

Optimal stimulation parameters for therapeutic effects

Long-term safety of intravascular electrodes

Efficacy compared to traditional VNS

Durability of clinical benefits

Cost-effectiveness

Several companies are developing endovascular neuromodulation platforms, suggesting this approach may reach clinical practice within 5-10 years.

Key Takeaways:

Endovascular VNS stimulates the vagus nerve from inside the internal jugular vein

The approach eliminates the need for open surgery

Recovery time drops from weeks to days

Selective targeting may reduce side effects like hoarseness

Positioning within the vein is critical for effectiveness

This represents a paradigm shift toward minimally invasive neuromodulation

The vagus nerve has been called the "highway to the brain." Endovascular VNS may finally make this highway accessible without the roadblocks of surgery.

"We're moving from an era where neuromodulation required surgeons to one where interventional cardiologists and radiologists can deliver the same therapy through a catheter. That's a transformation that will expand access to millions of patients."