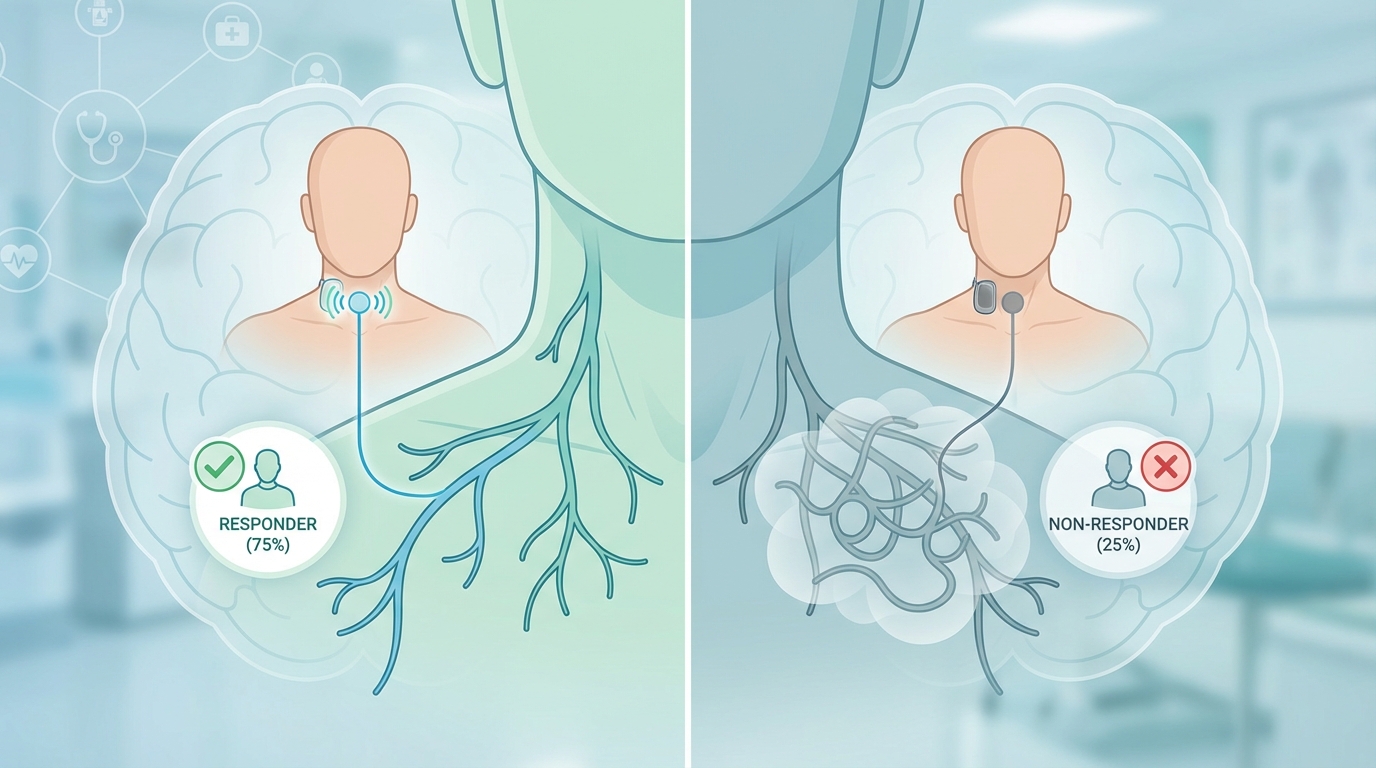

The Hidden Anatomy Problem: Why 25% of VNS Patients Don't Respond

And how ultrasound imaging is revolutionizing precision vagus nerve stimulation

Research Source: Nature Scientific Reports 2023, Journal of Neural Engineering

Reading Time: 9 minutes

Key Topics: Cervical vagus nerve anatomy, ultrasound measurement, surgical outcomes

25.4% of VNS patients receive no measurable benefit from implanted devices

Imagine undergoing surgery to implant a $30,000 medical device, only to discover months later that it's doing absolutely nothing for your condition. This is the reality for more than one in four patients who receive vagus nerve stimulators — not because the technology doesn't work, but because of a problem that until recently, surgeons couldn't see.

The cervical vagus nerve — the target for all VNS therapies — is one of the most anatomically variable structures in the human body. Its size, position, and relationship to surrounding structures differs dramatically between individuals. Yet for decades, surgeons have been implanting standardized cuff electrodes using anatomical landmarks alone, essentially operating blind to the specific nerve they're targeting.

New research published in Nature Scientific Reports reveals the shocking extent of this variability — and points to a solution that could transform VNS from a hit-or-miss procedure into a precision therapy.

The Carotid Sheath: A Crowded Highway

To understand the challenge, we need to visualize the surgical field. The cervical vagus nerve doesn't travel alone. It's bundled with the internal jugular vein and common carotid artery inside a fibrous envelope called the carotid sheath — essentially a neurovascular highway running up each side of your neck.

Within this sheath, the three structures maintain a generally consistent relationship: the internal jugular vein lies laterally (toward the outside), the carotid artery sits medially (toward the center), and the vagus nerve typically runs posteriorly, nestled between them. But here's where "typically" becomes problematic.

Anatomical Variations That Change Everything

Research by Dörschner and colleagues at the University of Leipzig analyzed the cervical vagus nerves of cadaveric specimens using high-resolution ultrasound, direct casting, and histological examination. Their findings reveal stunning variability:

Anatomical Feature Range of Variation Clinical Impact Nerve position in sheath Anterior, posterior, lateral, or medial to vessels Affects surgical access and electrode placement Cross-sectional area (CSA) 2.2 - 5.7 mm² across studies Determines cuff electrode sizing Distance from skin surface 10 - 30 mm depending on body habitus Affects transcutaneous stimulation efficacy Fascicular organization 1-12 fascicles varying in size Influences fiber type recruitment Branching patterns Variable motor/sensory branch points Determines side effect profiles

The Cross-Sectional Area Mystery

Perhaps the most critical finding concerns nerve diameter. Cuff electrodes — the metal collars wrapped around the vagus nerve during implantation — come in standard sizes. If the cuff is too large, it slides around, creating inconsistent electrical contact and potentially damaging the nerve through mechanical irritation. If it's too small, it compresses the nerve, blocking blood flow and causing ischemic damage.

Here's the problem: multiple ultrasound laboratories have published "reference values" for normal cervical vagus nerve cross-sectional area, and their results are all over the map:

Lab A: Mean CSA 2.2 mm²

Lab B: Mean CSA 3.8 mm²

Lab C: Mean CSA 5.7 mm²

That's a nearly three-fold variation in what's considered "normal." When surgeons select a cuff size based on population averages rather than individual measurements, they roll the dice on whether the fit will be appropriate.

The Cuff Sizing Dilemma: Current VNS devices offer cuff diameters typically ranging from 2-3 mm. But the actual nerve diameter (derived from CSA) varies from 1.7 mm to 2.7 mm. A mismatch can lead to complete therapy failure or nerve damage.

Ultrasound: The Missing Piece

High-resolution ultrasound offers a non-invasive solution to this anatomical uncertainty. Using frequencies of 10-18 MHz, modern ultrasound systems can visualize the cervical vagus nerve with sub-millimeter resolution, revealing:

Exact nerve location within the carotid sheath

True cross-sectional area for precise cuff sizing

Fascicular pattern (sometimes visible as internal echoes)

Relationship to vessels for surgical planning

Anatomical variants that might complicate surgery

The Leipzig study compared ultrasound measurements against the gold standard of direct casting and histology. They discovered that ultrasound tends to overestimate nerve diameter by 15-30% due to the inclusion of surrounding connective tissue and partial volume effects. However, with proper technique and correction factors, ultrasound can provide clinically useful measurements that are far superior to anatomical guesswork.

Preoperative Ultrasound Protocol

An ideal preoperative ultrasound examination for VNS planning includes:

Patient positioning: Supine with neck extended and rotated slightly away from the examination side

Transducer selection: Linear array, 10-18 MHz for optimal resolution

Scanning technique: Transverse and longitudinal planes from clavicle to hyoid bone

Measurements: CSA at 3-5 levels, documenting maximum and minimum diameters

Documentation: Images showing nerve position relative to vessels, annotated measurements

Correlation: Comparison with contralateral side if considering bilateral approaches

The 25% Non-Responder Problem

Let's return to that troubling statistic: 25.4% of VNS patients show no measurable benefit from their implanted devices. While some non-response is expected in any neuromodulation therapy, this rate suggests systematic problems beyond patient selection.

Several anatomical factors likely contribute:

1. Cuff-Nerve Mismatch: Inappropriate electrode sizing creates poor electrical contact, delivering subtherapeutic stimulation to target fibers while potentially activating unwanted nearby structures.

2. Anatomical Variants: Aberrant nerve paths, unusual branching patterns, or atypical fascicular arrangements may place therapeutic fibers outside the electrical field generated by standard cuff placement.

3. Surgical Variability: Without preoperative imaging, surgeons rely on exploration to locate the nerve. The segment selected for implantation may not be optimal for therapeutic effect.

4. Position Instability: Poorly fitted cuffs can migrate over time, losing contact with the nerve or shifting to suboptimal positions.

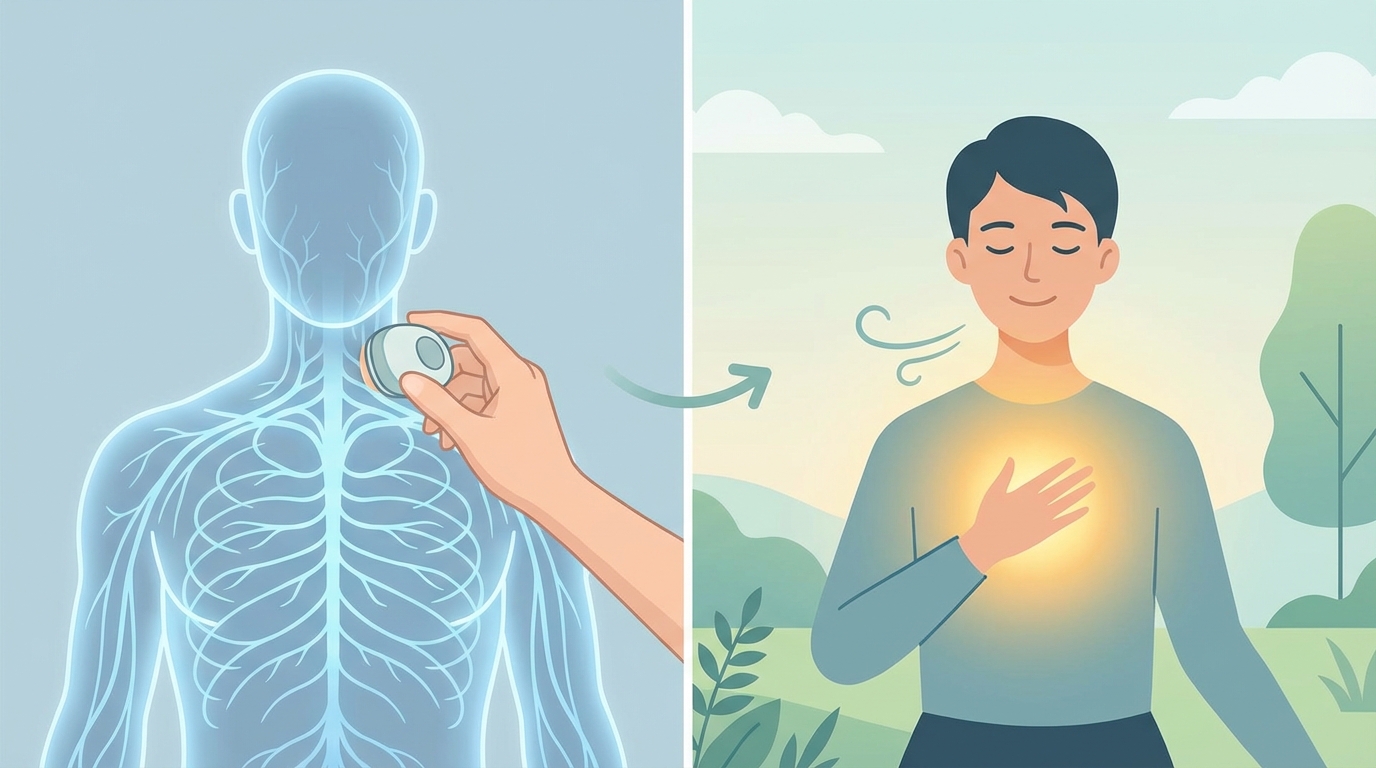

Beyond Implantation: Ultrasound for Non-Invasive VNS

The implications of this research extend far beyond surgical planning. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS) — the non-invasive alternative to implanted devices — depends entirely on accurate targeting of the cervical vagus nerve through the skin.

Current tVNS devices typically use anatomical landmarks ("place electrodes over the carotid pulse and move laterally") or simple positioning instructions. But given the variability in nerve depth, position within the sheath, and relationship to vessels, these approaches are hit-or-miss.

Ultrasound-guided tVNS represents the next evolution. Using real-time imaging, clinicians can:

Visualize the exact nerve location before applying stimulation

Position surface electrodes for optimal nerve activation

Verify that stimulation is reaching the target (via HRV or other physiological markers)

Avoid stimulating the carotid sinus (which can cause dangerous blood pressure drops)

Account for individual anatomical variations

The Future: Personalized VNS

As VNS moves from a one-size-fits-all procedure to a precision therapy, ultrasound will play a central role. The vision includes:

Preoperative Planning: Every patient receives high-resolution neck ultrasound to map their vagus nerve anatomy, select optimal cuff size, and plan surgical approach.

Intraoperative Guidance: Surgeons use ultrasound to confirm nerve identification, guide dissection, and verify proper cuff placement before closing.

Postoperative Monitoring: Follow-up ultrasounds assess cuff position, detect migration, and evaluate nerve integrity.

Non-Invasive Optimization: Ultrasound-guided tVNS becomes standard of care, with patients receiving personalized electrode placement based on their unique anatomy.

Key Takeaways:

The cervical vagus nerve shows dramatic anatomical variability between individuals

Cross-sectional area varies nearly 3-fold in "normal" populations

25% of VNS non-responders may result from anatomical mismatch rather than treatment resistance

Preoperative ultrasound can measure nerve size and location for precision cuff selection

Ultrasound guidance transforms tVNS from guesswork to targeted therapy

Personalized VNS based on individual anatomy represents the future of neuromodulation

As research continues and ultrasound-guided techniques become standard, we may finally see that 25% non-responder rate drop dramatically. For patients suffering from epilepsy, depression, and inflammatory conditions, that's not just an academic improvement — it's a life-changing advance.

"The vagus nerve is not a standardized cable with predictable dimensions. It's a living, variable structure that demands personalized approaches. Ultrasound gives us the eyes to see what we're doing."